“So you are sure you don’t want to take a rifle?” The outfitter looked at me with some skepticism.

“Yeah, I’m OK with just the longbow.” My guide, Bruce, expressed his consent: “A man after my own heart!” That was it then, we made our bed. Bruce and I loaded our stuff into the RAV4, nodded good-byes, and headed west.

Two months earlier I had joined the Life Member breakfast of the Alberta chapter of the Wild Sheep Foundation. The main attraction for this event was not the bacon and eggs, but a draw for a tahr or chamois hunt in New Zealand. The morning had gone by most like any other fundraising event that I have ever attended – the admission to these events is mostly a donation; it is something you never dream about winning – until the last name was drawn, and it was mine! The unimaginable had happened, I had won a hunt.

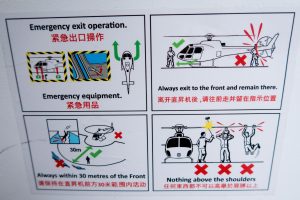

Fourteen weeks later on a Sunday I landed in Queenstown, and was picked up the next morning for the drive to Wanaka and the lodge of Exclusive Adventures, the donor of this hunt. We wasted little time on formalities and drove for about four hours to the West coast of the South island, to meet the chopper at three. We would be hunting a Wilderness Area, where helicopter access is regulated by an application and draw process. These areas are divided into so-called ballot blocks, and only one party at a time can hunt a block. We’d be the last party in. There was another way of accessing the same area: about two and a half days of hiking along a boulder-strewn river bank, not feasible giving our tight time frame. The chopper ride can be seen as the equivalent to driving into hunt camp in North America. All hunting from there would be on foot, climbing into the alpine, where we were hoping to find tahr.

I was surprised to hear that we were scheduled to fly out Friday morning. Initially the weather forecast was brought up, but later I learned that Friday was the last day that flying was allowed in that area. So basically we would have three full hunting days, plus whatever we could accomplish on the day we flew in, which, due to the short hours of daylight around the winter solstice, was not much. A tall order for a rifle hunter perhaps, it felt like we would need some serious endowments of luck by the hunting gods to pull this off with the longbow.

Bruce called the treed area around camp and everywhere on the lower slopes “beech forest”. The beech tree in New Zealand couldn’t have been more inaptly named. Whereas in Europe and North America a mature beech forest generally has little understory because of the light-blocking effect of the beech’s layered branch structure, the Kiwi beech tree is gnarly and lets through plenty of light and moisture for many species of unspeakables to grow on the bottom. A beech forest therefore is not the stately, almost groomed-looking affair that you might imagine, but more what you would refer to as a jungle; on a steep mountain side. Monday afternoon we fought this “scrub” to no avail; light left us before we reached any kind of view point. Tuesday morning we started up a “spur” close to camp, immersing ourselves in the dark and tangled vegetation before first light, picking our way up a game trail. As the ferns of the lower country became less ubiquitous, the trail got narrower. From time to time we’d bump into an overhanging rock, a “cave”, below which a carpet of droppings showed that tahr regularly use these hidden spots to wait out inclement weather. They were also the only flat spots on the entire mountain, it seemed.

Every few steps, small branches would lodge itself between string and bow limb. Every twenty steps hands were required to climb across a particular steep section, over a fallen tree, or to hold onto some piece of vegetation, while balancing on the edge of a cliff on top of some low-growing woody shrub. Sometimes the trail actually consisted of plants growing up and over a semi-vertical face. Through the branches you could see light come up from a long drop to death or dismemberment.

But the hunt was young, our strength intact, and hopes were high. After a few hours the trees grew further apart, going got easier, and finally that moment that every true mountain hunter longs for arrived: we broke out of the green zone, and looked upon the alpine! We found a spot to sit down, put on a jacket, eat and drink something, and glass the slopes. Before long a young bull tahr appeared on the opposite ridge. Beautifully backlit by the rising sun he showed off his mane fluttering in the wind, before dropping back down, and out of our view. With no other animals in sight, we decided to climb downwind and circle around, to see if any others would be feeding in the morning sun where the bull had been. As we crested, we overlooked a big avalanche chute with no vegetation growth in it. Despite our efforts to go slow and sneaky we spooked the young bull a bit later and watched him disappear into the trees out of which we had emerged an hour earlier. We completed our circle and had lunch.

After our break we headed up to a large ice field above us, and armed with crampons and ice axe we gingerly made our way across several chutes towards a large creek drainage. From there, we had new terrain to glass, and found a bull tahr and several nannies in the scrub underneath a craggy ridge. Not really able to judge how steep the terrain was in which they were bedded from where we were, and unable to make a direct unseen approach, we decided we’d try that area the next afternoon. I ranged the bull just for giggles: 300 yards. Challenging with the wind we were experiencing, but not impossible with a rifle; a day and two buckets of sweat away with the bow.

We retraced our steps, and found camp by the light of our head lamps. Dinner, coffee, and a few short stories later we retired early for a long night in the tent. Something fairly comfortable to lie on would be a must for a hunt at this time of the year, with darkness lasting longer than daylight, in conditions too wet to reliably find firewood.

After savouring my favourite backpacking breakfast, Heather’s Choice Cherry Cocoa Nib – although I do not know what a nib is – and a Via coffee, which I much preferred over the “tea bag” coffee solution that Bruce provided, the river bed loomed dark and unfriendly. Big boulders occasionally blocked our way, so we took our time finding the right creek to climb up. After a while the obvious edge of an earlier avalanche became visible, a wall of ice covering all of the creek bed. I tried to remember what the avalanche course book said: if there has been an avalanche already, there is less chance of another one, or if you are in a proven avalanche path, get out, because you may get another one.

We crossed the head of the avalanche run out quickly and got up the side of the chute, away from possible harm. Conditions looked fairly stable anyway, as far as I could tell (no fresh snow dumps on top of slippery layers, no wind slab accumulation). One thing to consider with respect to snow and avalanches, different from what I have encountered in the Eastern Rockies, is that where we were, significant slabs of snow and ice accumulated on top of very springy vegetation that covered large areas. Sometimes we’d break through and large chunks of ice would start sliding. Something to be careful with on steep sections.

We crossed the head of the avalanche run out quickly and got up the side of the chute, away from possible harm. Conditions looked fairly stable anyway, as far as I could tell (no fresh snow dumps on top of slippery layers, no wind slab accumulation). One thing to consider with respect to snow and avalanches, different from what I have encountered in the Eastern Rockies, is that where we were, significant slabs of snow and ice accumulated on top of very springy vegetation that covered large areas. Sometimes we’d break through and large chunks of ice would start sliding. Something to be careful with on steep sections.

We climbed up to the ridge and pulled out the glass. It didn’t take long to find a bull, two nannies and a kid in the creek below us about 200 yards out. The bull tried his best to get one of the nanny’s attention, this being the tail end of the rut, but she kept evading him. After a while it became apparent that they were slowly drifting uphill, and maybe they’d end up in terrain where we could try a stalk.

As we were contemplating moving uphill too, we heard the sound: the rhythmic bobbing of a helicopter. From far downstream we could see the chopper work its way towards us, weaving in and out drainages as he went. Through the binos we saw a tahr suspended from a sling underneath the chopper. In this area heli hunting (AATH – Aerial Assisted Trophy Hunting) was not allowed and though we had no proof on how the tahr was obtained, this guy was obviously not just flying from A to B, but looking for something. Our tahr didn’t enjoy the disturbance any more than we did, and they retreated into the scrub. Another little band to put on our to-do list for another day.

As we were contemplating moving uphill too, we heard the sound: the rhythmic bobbing of a helicopter. From far downstream we could see the chopper work its way towards us, weaving in and out drainages as he went. Through the binos we saw a tahr suspended from a sling underneath the chopper. In this area heli hunting (AATH – Aerial Assisted Trophy Hunting) was not allowed and though we had no proof on how the tahr was obtained, this guy was obviously not just flying from A to B, but looking for something. Our tahr didn’t enjoy the disturbance any more than we did, and they retreated into the scrub. Another little band to put on our to-do list for another day.

It was time to retreat, get “a good feed”, and go look after the tahr we left on the mountain the previous afternoon. There were three distinct knobs on that spur and we had seen them bedded underneath the third. A long and steep, mostly fern-covered slope led us up to the ridge. The hard work was over, the tricky parts were still to come.

Words are hard to find to describe the terrain we were in, and pictures probably don’t do it justice either. We snuck along a knife-edge ridge, sometimes bare, sometimes overgrown. We crested the first knob, and found no animals on the other side. It’s good practice not to sky-line yourself to much, but in many spots we had no choice; the only way forward was right along the ridge, with long drops on either side. Past the second knob again no tahr. We noticed a narrow trail cutting into the scrub underneath the third knob, leading to an overhang.

We had to use all-fours, and ice axes to climb up to the trail, and I needed a minute to compose myself before taking the bow off the pack and starting a very careful shuffle towards the rock. A distinct game smell was on the breeze, clearly we were right in their living room. I made it to the overhang, underneath of which a thick carpet of tahr droppings provided proof that we were in the right place. Bruce had seen a nanny and kid move downhill before I got there. I went on alone to another outcropping, but found nothing but vertical terrain behind it. Even if there had been a world record bull tahr standing there, I doubt I could have nocked an arrow and drawn the bow without the forward lean in my form causing me to plunge to my death.

Gingerly I turned around, and without speaking and fully concentrated on the descent we retreated to the fern covered slope. Our smiles were a little broader than usual once we were able to sit down and take off our packs for a break: a bit of relief mixed in with the excitement of the climb.

The morning of the last hunting day we woke to a cold and frosty morning. Overnight, the rocks got covered in an invisible sheet of ice, making walking along the river and in the creek beds very treacherous. After a long haul along the river, at the start of the drainage where the chopper spooked the tahr, we found a very convenient shoulder with little vegetation on it on the right side of the creek, and we climbed it slowly, stopping often to glass both sides. The lower slopes were a mixture of bush and grassy bits, so it was easy to overlook an animal or two or even a small mob (Kiwi parlance for a group or animals). We found some nannies on a steep overgrown cliff right where the creek bifurcated. They would see us moving readily enough, so we hunkered down and waited for developments.

Soon enough Bruce spotted a bull on the opposite bank of the creek, right where the grey of the rocks gave way to green shrubbery. That was our chance! If we could get back to the creek unseen, we could climb to within 100-120 yards or so, and use the lay of the land to keep us hidden till we were inside of thirty yards. Or so we hoped. We bailed off our side of the creek without delay, and twenty minutes later I was taking off my pack, putting my ice axe away, and nocking an arrow. Under eighty yards we estimated, and Bruce stayed behind as I angled uphill and upstream.

I peeked over and saw the bull still bedded right beside a bush. I turned and gave a wink to Bruce, indicating that “it was on”. Going was quiet on the grass-covered rocks, the wind was downstream, everything was perfect; until an alarm whistle sounded somewhere above me! Some hidden tahr had spotted me or Bruce or both of us and didn’t like our being there. Things just got a whole lot more difficult. As quickly as I could without making sound – to my ears anyway – I closed the distance to the last rise. Just before I got there I heard a wheeze. Not good. I put tension on the string, and took one more step.

The bull was on the move, 25 yards out, and quickly jumped out of the little gully into some bush. He stopped, presenting me nothing but his behind to look at. Thirty yards. If only he turned. Before I could consider a desperate action, he slipped down, and reappeared seconds later, ten steps higher up the hill. Now he was close to forty yards out, showing only the relatively narrow front of his chest. I had drawn when he popped up, but had to let down, realizing that this was not the opportunity I had been looking for; just too far, too small a target. He slipped back down into the bush, and more tahr started whistling above us. I quickly ranged where he had been: 40 yards indeed.

We figured our best chance had just come and gone, but there was still a lot of daylight. Instead of heading back down, we continued uphill to a spur, and crossed it to get into the creek with the avalanche ice in it. The descent through that creek bed proved hazardous, as the overnight ice had not yet melted off the rocks. Bruce fell and hurt his arm, and I did a headfirst dive towards a pool, stopping with my face inches from a rock. That’s probably where I lost the crampons out of my pack.

Not wanting another go at the icy rocks, after a copious meal – both of us had entered the stage where we were eating like horses – we climbed up through the scrub behind camp.

I was starting to feel a little tired, but it was our last afternoon. We were hoping to catch some tahr in the open bush near the tree line but no such luck. We climbed on and found a bull and some nannies above us feeding. Closing to gap unnoticed to about 100 yards was not a big chore, but the crunchy snow, and general noise made by climbing through the low-growth vegetation made that we could not get any closer.

I was starting to feel a little tired, but it was our last afternoon. We were hoping to catch some tahr in the open bush near the tree line but no such luck. We climbed on and found a bull and some nannies above us feeding. Closing to gap unnoticed to about 100 yards was not a big chore, but the crunchy snow, and general noise made by climbing through the low-growth vegetation made that we could not get any closer.

Glassing around revealed another mob of tahr. One young bull was feeding, and two mature bulls were standing over a bedded nanny. In the rut, bull tahr stand watch over nannies that they suspect might be ready for breeding for a long time, sometimes hours. We watched both mobs for about an hour, realizing that the second group was exactly in the location where we had sat the first morning. Right place, wrong time.

With light fading we made our way down the spur towards camp. Little of this terrain allows you to take your mind off business for very long. Even in the trees, a misstep can bring serious harm, or in some spots worse. With fatigue setting in, I was definitely less footsure than on the first day. We made a big meal out of left-over bread, cheese, salami, and freeze-dried meals, including an “ice cream” desert of questionable taste and consistency. The apple pie we had the night before had been the better choice.

The chopper arrived ten minutes early the next morning. We were ready. Just an half hour earlier, two choppers had flown in to pick up a group of hunters across the river from us. The pilot indicated we might be the last load of the day. Unbeknownst to us, low clouds had moved in on the other side of the mountains. Once we rose over the crest, a blanket of fog covered the low country, with only the highest peaks showing. We found a little hole in the clouds close to a cliff, and with two descending circles the chopper managed to drop through it and find a clear flight path back to the base.

The adventure was over. Not much left to do but drive back, dry out some gear, spend a night at the lodge, drink a few beers, waste some time in Queenstown and dread the long flight home.

What the trip lacked in duration, we made up in intensity. We hunt the mountains for the sheer joy of being out there, where the air is thin, and the drops are long. We welcome the challenges and accept the notion that during some trips the Grim Reaper is watching out of the corner of his eyes. Sometimes the hunting gods smile and grant us a chance, and that’s all we ask for. The memories come home, and long after our knees have buckled and our backs are no longer straight, we relive the days when we hunted the high country.