“Do you think Aika will be able to find my deer?”

We were standing on a cut line in the municipal forest where my uncle leased the hunting rights on some 700 acres. My cousin had shot a small buck that had jumped off the trail into a stand of immature pines. Thick stuff. He’d looked in the first rows of trees, but found no sign. So he backed off and waited for me to show up after the morning sit.

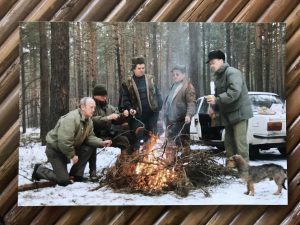

Aika was a German Hunting Terrier, six months old. I had picked her up at a breeder near Hannover, Germany in late winter. The pups were born in a small unheated kennel in the heart of winter. There were six pups. More had been born, but the breeder had killed them, because he “didn’t want to deal with bottle feeding”. She was so small, fitting into a shoe box. Hard to see at the time how she would grow into a fierce little hunter, flushing pheasants from thorny cover that bigger dogs couldn’t (or wouldn’t) enter, retrieving anything up to the size of a big hare, crazy about working in water, never losing the drive to hunt during long, taxing days in the field. But that was still uncertain future when we were zipping West across the Autobahn, with a furry bundle in my wife’s lap.

Aika and I had barely moved beyond training on continuous-drag scent trails to a trail with discrete drops (more like small gushes) of blood. She’d been doing just fine, but it was all still pretty playful; short trails in easy terrain with no distractions. After all, at six months old, she was still all puppy-brain.

“Do you think Aika will be able to find my deer?” my cousin asked again.

“I don’t know. It may be asking a lot of her, but let’s try.”

We drove back to the cabin to pick up the little munchkin. About 90 min later I rolled out the long line, trying to relax and send calming vibes to the bouncing pup at my feet. As we walked up to the first blood, beyond where the yearling buck had been standing, the change in the dog was striking. She went from playful to business in a heartbeat. During practice sessions on a fake trail she usually was borderline disinterested, but now it was all concentration.

With a final confirmation from my cousin about the direction the buck had disappeared we entered the thicket. About 30 feet in, the little dog sniffed up a clot of blood. Perhaps 100 feet beyond that, she found a patch of bloody hair, rubbed onto a tree. This was actually working! Five minutes later I was not so sure. Aika lost intensity and started meandering. We were off the trail.

I took her back to the beginning for another try. She pointed out the same blood, and the same hair, but again lost interest a little later. It was just too much to ask for such a young and relatively untrained dog. We started to circle back to the cutline, when Aika took a sharp left and pulled hard. I almost told her to stop playing around, but something told me to give her a little more time and trust. Moments later we were standing next to the dead buck.

Opportunities to work on lost or wounded deer don’t come very often. Aika’s star really shone brightly when hunting small game. I fondly remember so many great retrieves of pheasants, ducks and hares, that I gladly forgive her for the time she made me swim out into a beaver pond. She had not found the duck but instead had grabbed onto a branch, and was determined to retrieve it, even though it was attached to the beaver’s lodge. Her tiny brain had momentarily locked up, and I was afraid she’d drown before letting go. I swam out, and she cheerfully greeted me, happy for the support. With mixed emotions I pushed her into the direction of the duck that floated a ways beyond the lodge. We swam the loop around the pond, she picked up the duck and after some drying off we continued to hunt.

Unfortunately Aika died too soon at the age of nine. Kidney failure. I still miss her.

F.