The alarm went off at an ungodly hour, and it took a quick shower to get some of the haze out of my head. I don’t know who these people are that jump out of bed straight into their boots, and are ready to go, and I don’t understand how they do that. Regardless of what the day ahead has in store, waking up is a process for me. With joints creaking I took the dogs out for a quick one, and slowly the blood started pumping and the brain geared up.

It was a long dark drive to the lake I had scouted out in the spring, and this being opening day, I feared I’d show up at the sandy staging area on the North side a little late, with other hunters out on the water before me. This sneak approach really only works if you are the only one, or the first one, to paddle along the reeds.

I needn’t have worried, nobody was there. It was still cold, and the last of the fog was rising off the water as I set off. In spring the marsh had been full of sound of ducks and geese. It was a lot quieter now. The 20ga loaded with steel shot #4s rested on my right, and slowly I paddled the meandering water. When a couple of teal came soaring past, I dropped the paddle, grabbed the gun, swung, and missed twice. Not a great start.

A little later I happened upon a pair of teal, that took off as soon as I came around the bend, and I managed to drop one! As the morning progressed I added three more to the tally, before I ran out of suitable water. There had been some gun shots on the south side of the lake but otherwise I had the place to myself. Plenty happy with my modest harvest I drove home.

That night we had a wonderful dinner of pan-seared duck breasts. Ducks make a fantastic meal, if treated right, meaning searing it on high fire and briefly. You want, no must have, the insides still pink, or risk the meat turning dry and livery.

We ate this with ciabatta bread, oven-roasted tomatoes and onion, and a balsamic reduction drizzle (that’s nothing more than balsamic vinegar mixed with brown sugar, allowed to simmer for a bit to make it thicker). It was fantastic!

A week or so later I repeated the routine, hitting up a larger reservoir that has, according to Google Earth, lots of bays and islands on the East side. I’d love to report about my shooting prowess, how I plucked the ducks and geese from the sky with ease, but that would be lying. Two double misses started the morning, but luckily I was up for some redemption and ended the day with a tally of six ducks. The number of shots fired will hopefully fade from memory, as my brain chooses to remember the highlights of the day only.

This is not a way to get big bag limits, and it was never intended that way. But it allows quiet time on the water, taking in the sights (like the two otters I saw on the first outing), relaxing through the morning, and potting the odd bird for dinner. It’s nice too to vacate the water before noonish, as this is generally a day resting area for birds, migrating birds in the latter half of the season, and they need their quiet time too.

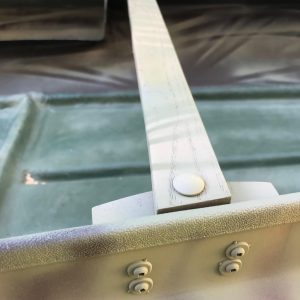

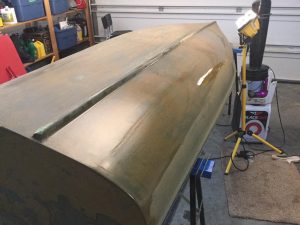

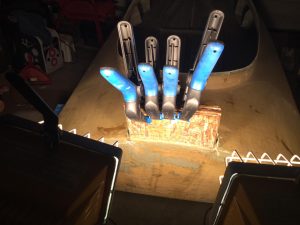

And that’s it. Project Duck Boat finished, but in a way it’s just beginning. We have a month or so left of open water, suitable for such a little boat. I have no intention to fight the fall storms and freezing water. I can get hypothermic in other places without the risk of drowning. Next spring, pike will be waiting in the reeds, to eat the fly that I will present to them.

Good times!

Seven years ago when I started drawing for mule deer I had no intentions of bow hunting, much less with a recurve. I’ve held this tag 3 times before and shot decent bucks and the zone has potential for some big deer, but to get a deer with my bow has become somewhat of an obsession lately and size doesn’t seem to matter now. Opening day was coming soon and Frans was going to be busy scouting for his moose tag, so I got a hold of my buddy Derick Heggie and he was more then happy to come along. He’s recently started in archery hunting as well with a compound and was bringing his bow along too, in case we happened across any does; you can buy a general archery doe tag in this zone.

Seven years ago when I started drawing for mule deer I had no intentions of bow hunting, much less with a recurve. I’ve held this tag 3 times before and shot decent bucks and the zone has potential for some big deer, but to get a deer with my bow has become somewhat of an obsession lately and size doesn’t seem to matter now. Opening day was coming soon and Frans was going to be busy scouting for his moose tag, so I got a hold of my buddy Derick Heggie and he was more then happy to come along. He’s recently started in archery hunting as well with a compound and was bringing his bow along too, in case we happened across any does; you can buy a general archery doe tag in this zone.

Nothing showed that morning, and I tried another area in the afternoon. Much walking and a lot of glassing revealed nary a deer, until I almost stupidly walked in full view of a bedded buck. Distance and luck kept me from spooking him, and I froze until I was sure that he hadn’t spotted me. Lying right underneath the edge of a shallow draw, with the wind in his back, approaching him would be tricky, but I decided to try just the same.

Nothing showed that morning, and I tried another area in the afternoon. Much walking and a lot of glassing revealed nary a deer, until I almost stupidly walked in full view of a bedded buck. Distance and luck kept me from spooking him, and I froze until I was sure that he hadn’t spotted me. Lying right underneath the edge of a shallow draw, with the wind in his back, approaching him would be tricky, but I decided to try just the same. Long story short, I got to within 70-80 yards or so but decided to break off the stalk. I’d either stay out of sight but would have the wind in my back, or I would have to crawl closer through his peripheral vision. Coming back the next day seemed like a better plan.

Long story short, I got to within 70-80 yards or so but decided to break off the stalk. I’d either stay out of sight but would have the wind in my back, or I would have to crawl closer through his peripheral vision. Coming back the next day seemed like a better plan.